One might assume that a film titled Oppenheimer would center largely on the creation of the superweapon that brought about the end of World War II, and although this assumption would be correct, one might find themselves ill-prepared for just how much of Christopher Nolan’s latest film is not about that particular sequence of events. That’s not to say significant screentime isn’t devoted to the Manhattan Project — the construction of the Los Alamos Laboratory, the assembling of the best physicists in the world, and the ever-mounting pressure of trying to beat the enemy to the finish line is all here — but Nolan is equally fascinated with later events in the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, portrayed here by Cillian Murphy in the most captivating performance of his career.

Those post-war events include a 1954 security clearance hearing, where a hand-picked panel of political hitmen dissect decades of Oppenheimer’s relationships and decisions in a transparent effort to discredit and humiliate him; while a certain former President of the United States frequently shouts into the echo chamber about witch hunts, he and his followers might be well-served by brushing up on their history to see what this actually looks like in practice, and the kangaroo court proceedings to which Oppenheimer was subjected stand as a textbook example.

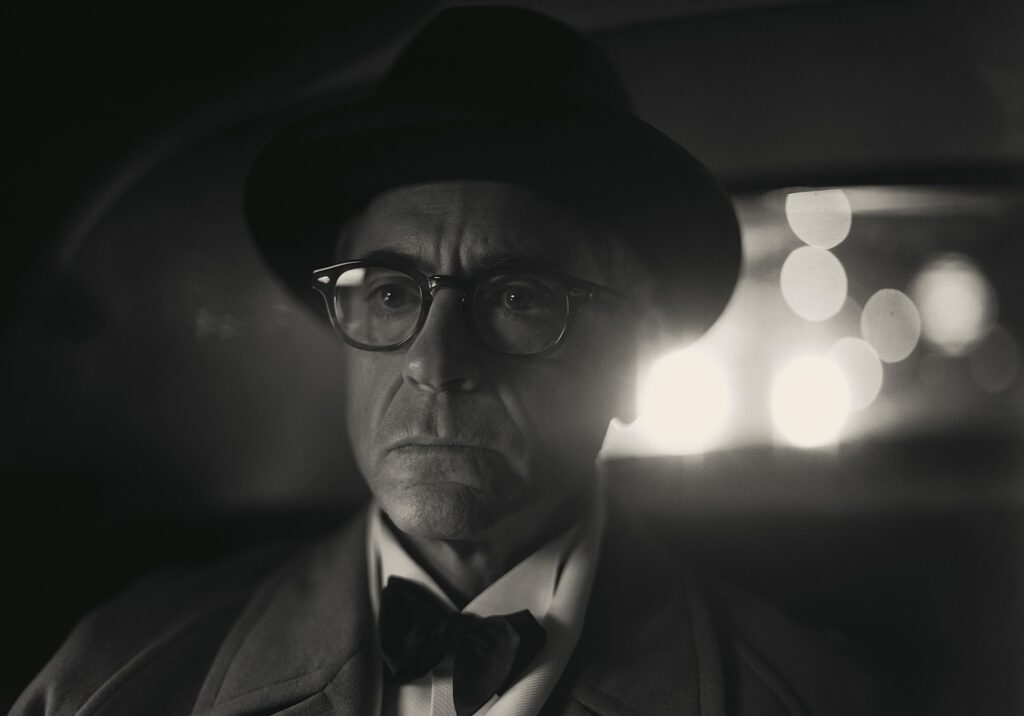

Also on Nolan’s mind is a 1958 congressional hearing to confirm Lewis Strauss as Eisenhower’s Secretary of Commerce. Shot on specially made black-and-white IMAX stock, these gorgeous sequences also hide the film’s secret weapon: no longer tethered to the Tony Stark persona that helped build the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Robert Downey Jr. (as Strauss) sets the screen ablaze with some of his most ferocious work. We’ve been watching Downey quip and smirk his way through superhero fare long enough to forget that he’s one of the finest actors of his generation; his performance in Oppenheimer is here to jog our memories, and he’s surrounded by one of the most impressive ensembles in recent memory, with Matt Damon’s grouchy brigadier general emerging as my personal favorite.

Based on the non-fiction tome American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Nolan’s screenplay attempts to distill the staggering volume of information in Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s biography into these three segments of Oppenheimer‘s life, flitting from timeline to timeline in a way that feels haphazard at first, but pays dividends in the film’s final act by finding an emotional throughline in these seemingly disparate narratives. Some moviegoers have groused that Nolan’s penchant for nonlinear storytelling is a particular disservice here, but I would argue that arranging these same sequences in chronological order would blunt the impact of all three.

If there’s any disservice to be found here, it would be the film’s audio mix, which once again allows the score to overpower the dialogue. While not as egregiously imbalanced as Tenet, it still marks the continuation of a frustrating habit, and audiences experiencing the film in a theater with subpar sound equipment or poor acoustics will have their patience stretched to the limit. Equally vexing is Nolan’s apparent disinterest in writing complex female characters, a criticism that has plagued the celebrated director for years; Florence Pugh (as Oppenheimer’s lover, Jean Tatloc) and Emily Blunt (as his wife, Kitty) are given little to do except berate the protagonist for remaining stoic in the face of whatever adversity looms on the horizon. In the case of the former, it’s his decision to cut ties as he focuses on his work at Los Alamos and tries to be a better father and husband; in the latter scenario, it’s Oppenheimer’s refusal to fight back against the underhanded tactics deployed in the security clearance hearing that earns him Kitty’s ire. This does lead to an especially memorable moment, an all-too-brief scene in which Kitty is questioned by the committee, and Blunt knocks it out of the park. It’s a shame Pugh wasn’t given a similar opportunity to shine.

Thematically, Oppenheimer is arguably one of Nolan’s most complex achievements, a haunting portrait of a man whose unquenchable thirst to understand the fabric of the universe led to the creation of the very thing most likely to bring about its demise. “I don’t know if we can be trusted with such a weapon,” Oppenheimer tells a fellow physicist at one point. “But I know the Nazis can’t. We have no choice.” That singular belief, and the decisions made because of it, would bring about irrevocable changes that still reverberate today, and Nolan’s latest work arriving at a time when fear of nuclear destruction is at the highest level since the Cold War feels as poignant and darkly poetic as the work itself.