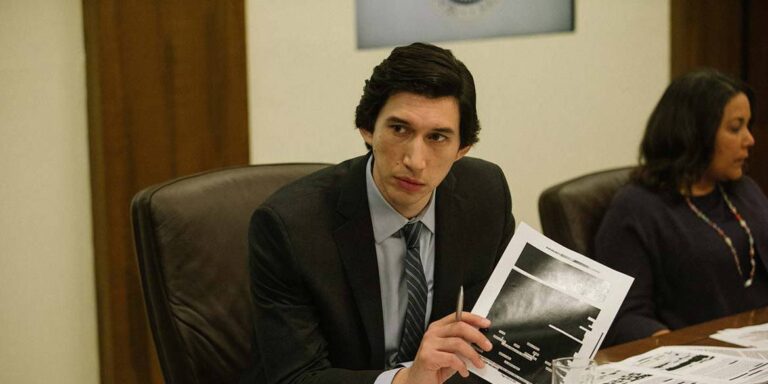

“It’s been very consuming,” says Daniel Jones (Adam Driver) in the opening moments of The Report. He’s just been asked about his work leading a Senate investigation into the CIA’s implementation of “enhanced interrogation tactics,” which were heavily relied upon when questioning suspected Al Qaeda operatives in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attacks. Jones is underselling it a bit: he spent more than five years combing through millions of pages of emails, phone records and documents, and the results of his investigation were compiled into the titular report, which spanned nearly 7000 pages.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves, so let’s set the stage: the New York Times has just revealed the CIA destroyed tapes of their interrogations of Al Qaeda detainees, and Senator Diane Feinstein (a brilliantly cast Annette Bening) wants to know why. She enlists Jones to spearhead the probe into the agency’s actions, and he gets to work in a fluorescent-lit basement office that doesn’t even have a printer. “Paper has a way of getting people in trouble at our place,” an agent tells him. “At our place, paper is how we keep track of laws,” Jones remarks dryly. The lack of basic office equipment won’t be the first time the CIA tries to hinder Jones’ investigation, as he frequently finding himself stymied by a government body which insists no wrongdoing occurred, yet refuses to make its agents available for questioning — sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

In fact, The Report shares a number of parallels and similarities with current happenings in the Senate, with members on both sides of the aisle bickering and pointing fingers and accusing each other of partisanship, rather than focusing on the actual evidence unearthed by the investigation. It’s a remarkable coincidence, and one that writer-director Scott Z. Burns couldn’t have foreseen — the film was shot in early 2018, and in that regard feels oddly prescient, serving as both a warning about the dangers of not learning from our mistakes, and an indictment of the political maneuvering and closed-door dealmaking that keeps leading the country down a similar path.

Although the bulk of the film takes place in offices and government facilities, Burns periodically whisks viewers away to clandestine CIA blacksites where a pair of former Air Force psychologists oversee the administering of techniques like sleep deprivation, mock burials, and waterboarding to elicit information from Al Qadea detainees. Brief though they may be, these sequences are horrifying and rage-inducing, particularly with the knowledge that the sustained torture of 119 detainees never produced a single piece of actionable intel. The acts themselves are unconscionable, but every bit as infuriating is the bureaucratic red tape which prevents Jones’ findings from being released to the public, as the current administration seems more concerned about maintaining the appearance of post-partisanship than about doing the right thing.

That Burns was able to distill 6700 pages of information into a two-hour film that’s fairly easy to digest is an impressive feat on its own, but it’s the dynamite ensemble cast that elevates The Report from rote investigative drama to nail-biting political thriller. Bening is pitch perfect as Senator Feinstein, and casting Ted Levine as CIA director John Brennan is a stroke of genius that lends an extra level of menace every time he appears onscreen. Michael C. Hall, Tim Blake Nelson and Matthew Rhys are all superb in small but pivotal roles, and as the center of the narrative Driver is positively masterful, a walking manifestation of paranoia, fury and righteous indignation. It’s a shame the film is being released in such close proximity to Driver’s next project, as the naturalism and authenticity of this performance will almost certainly be overshadowed by the capes and lightsabers just over the horizon.

Burns deserves commendation on a number of levels, but of particular note is his even-handed depiction of culpability on both the right and left. High ranking members of the Bush White House may have been responsible for greenlighting the new approach to interrogation and for publicizing wildly inaccurate claims of its effectiveness, but it was the Obama administration that sought to keep Jones’ findings from seeing the light of day. He even casts aspersions on Feinstein herself for the repeated hemming and hawing about taking action — The Report doesn’t quite paint her as a villain, because she ultimately makes the right choice, but the film stops well short of positioning her as a hero. Ultimately, Burns isn’t about to let either party off the hook, and at the heart of the film is a message about setting aside differences and working together to achieve something for the good of everyone — a message that we’d do well to remember today.

For more on The Report, click here to see our interview with writer-director Scott Z. Burns and former Senate investigator Daniel J. Jones.