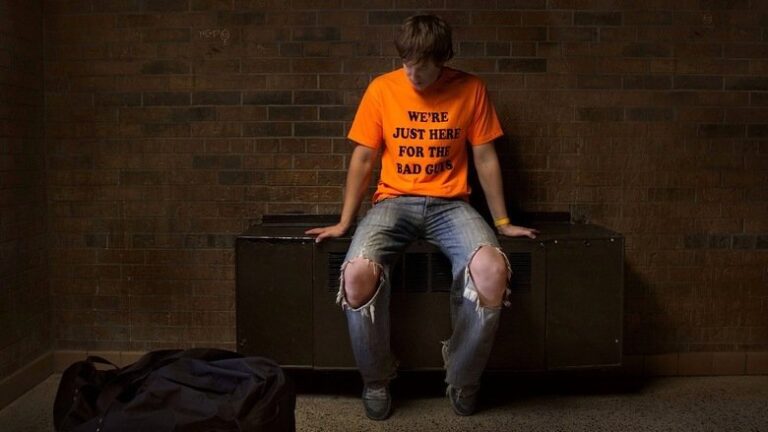

The Dirties, which took home the Grand Jury Prize at this year’s Slamdance Film Festival, is the riveting tale of two best friends who team up to film a movie about getting revenge on the bullies at their school. The narrative takes a darker turn when one of the boys seems to have difficulty separating reality from fiction, and may no longer be looking at the project as a joke.

Acquired by the Kevin Smith Movie Club and Phase 4 Films, the trailer for The Dirties was introduced to the San Diego Comic-Con audience during Smith’s annual Q&A session in Hall H, and was met with an overwhelmingly positive response. It continued to be recognized by film festivals as it played all over the world, and earlier this month was finally made available to the public with a VOD and limited theatrical release.

The film bravely approaches the subject of bullying and school violence from a seldom-seen perspective, and feels incredibly authentic in its characterization of modern-day high school students (check out our review of the film here). Director Matt Johnson, who also co-wrote the film and plays the leading role, was gracious enough to chat with us last week about the inspiration behind The Dirties, and what he hopes audiences will take away from the experience.

First things first – congratulations on picking up the New Wave Best Picture award at Fantastic Fest a couple weeks ago.

Were you there?

I was not. Unfortunately, I had to miss it.

It was amazing.

You’re starting to amass a nice little collection of awards.

You know, I think it has more to do with the subject of the film, the fact that it’s a movie about guys obsessed with movies. I think it’s easy for a lot of juries to be like “oh, they’re just like me.” But I feel very lucky.

You guys originally submitted to the Toronto Film Festival, and they passed on it, correct?

We begged them to screen it, because we’re all from Toronto and we’ve had our shorts play at TIFF before. I guess this movie was just too weird. To be honest, I don’t know what it was, but they really hated the movie.

Alright, so after Toronto, you submitted to Slamdance and got accepted. Was there ever a moment where you were like “fuck you, Toronto?”

No. [laughs] We were so naïve about a lot of this stuff. Before we’d screened anywhere, we didn’t think anybody was going to accept us, at all, period. We were just grateful that we were gonna get to screen this movie anywhere.

We were sad that Toronto didn’t want to screen the movie, and now that it’s done so well, we feel like [it was] a missed opportunity, because it would’ve been so great. But no, I’d never say “fuck Toronto.”

So you go out to your very first major festival screening, and you take home awards the first time a film plays for an audience. Did you feel a bit vindicated?

Yeah, because when Toronto passed on it, we were like “well, I guess our movie sucks.” And that was sort of the mindset that we took when we brought it to Park City, so it was amazing that people liked it and responded to it the way that they did. It was the last thing we expected.

You’re currently finishing school – how do you balance that with taking the film to so many festivals?

I’ve been lucky. Taking the movie to film festivals isn’t a ton of work. I’m able to do a lot of my school work there, so I was able to write a lot of my papers in the hotel at these film festivals. And at Locarno, Werner Herzog was receiving a special award, and one of my classes was on Werner Herzog, so I was able to interview him as a student for my big paper for Cinema Studies.

Although he was not so happy to be interviewed by me. I pitched him my idea for a movie, where we remake the film Looper, except starring me and him, and he liked the idea but it didn’t… the interview was very strange.

What’s been your most memorable experience from the festival circuit so far?

Fantastic Fest was probably the greatest. It’s my first time ever being in an Alamo Drafthouse before, that environment, and the fact that everybody there is writing about movies or making movies in some way. I’d never been that saturated with film lovers before, and when we won that award, it was just insane.

It’s got a lot of positive word of mouth. It’s such a different approach to that subject matter, it feels really fresh and original.

Film students, I think, have a kind of natural affinity for it. If you’ve ever made a movie on your own before, there are things that you can relate to. Maybe not everything, but certainly some of the things that Matt and Owen do.

Speaking of doing everything yourself, you guys shot something like 200 hours of footage.

Yeah, we shot it like a documentary.

When you’re working with that much raw material, how time consuming is it to sift through everything and put together the film you want?

It’s extremely hard at one level, but in terms of the actual amount of footage you have, it’s not that big of a problem, only because I was on set saying a lot of the dialogue and sort of coming up with it as we went. So I knew, when we went to look at footage, what would be good and what would be bad. So there’s probably sometimes like 100 hours of footage from The Dirties that no one has ever seen, including me. We just never watched it because I knew it was bad.

As you started putting together the ideas for the film, was there ever a scene that you wanted to include but decided to take out because it went a little too far?

There’s one scene in particular of me running headlong into a train that’s barreling down on me. It’s a real train, and I wanted to shoot this thing so audiences would see how crazy Matt was. He’s doing it as a joke, he’s running at this train that’s shooting toward him, but we couldn’t keep it in. It was just too insane. Too dangerous.

Any chance that was inspired by the “train dodge” scene in Stand By Me?

It was literally stolen directly from it, except rather than being like these kids are scared and trying to avoid it, Matt is like full-on running at it, almost daring himself to get hit.

What made you decide to tackle the subject of bullying and school shootings. Does this come from personal experiences?

I think a big part of it was that none of us had ever seen a school shooting film, or even a film about bullying, that accurately represented what our generation was going through. I thought that Elephant and Polytechnique and films like that were dealing with the subject matter, but not the people. The characters weren’t characters that I could relate to at all.

I think it was kind of our way of dealing with our unresolved psychological issues from what Columbine was to us, when we were young, which I never really saw done right in the media. The news sort of had its take, and then literature had its take, and then films about it were being made by much older people. I felt like, for me to have closure on that issue, I think I needed to make this movie.

When looking at the scenes in the film where we see Matt and Owen getting bullied – do these echo things that you went through personally? Or were you seeing other kids go through this, and wanted to give them a voice?

It was sort of a mix. Everything we used was either something that had happened to us or that we had seen – we didn’t invent anything for the movie. A lot of it was stuff that me or Owen had been through, or Josh or Evan, the other two writers, had been through. We didn’t really dress it up at all, we tried to make it exactly as we remembered it.

And some of the scenes we shot, when we looked at the footage we were like “oh, this is too ridiculous, this would never happen.” In fact, that scene where Owen gets slapped in the cafeteria? That comes from something where I was right beside with one of my friends when it was happening. And in real life, that scene went on for like another five minutes. The guy made him kiss his shoe, it was just the most excruciating thing I ever had to watch.

And we shot it. When you watch that footage, it seems like it’s made up, it’s so intense. So we actually had to scale back on a lot of the real stories, just to make it more believable. Which was kind of weird.

The whole subject of bullying just seems like something the public at large doesn’t want to deal with.

Not at all.

There was a lot of stuff in the Bully documentary that was extremely difficult to watch, and then to find out that people think it’s faked or set up is just kind of heartbreaking. People go through this kind of stuff every day, and it’s being swept under the rug or it’s being overlooked.

And I think people think it’s so clichéd, to a certain degree, and they’re not willing to believe it. Societal blindness for the intensity of a lot of this stuff is a part of the problem. You don’t believe that some of this stuff could be true, because who could be that cruel?

And we were sort of faced with that when making this movie. The cruelty that we remembered was even worse than what we presented, but for the sake of believability we couldn’t show it all, because of society’s denial of this issue.

I think you even see a little bit of that in the film, when Matt and Owen take the rough cut of their film and screen it for their teacher. Watching them act out this violent fantasy should be a giant red flag, but the teacher’s only concerns are that it’s too inappropriate to show in class.

Exactly.

I thought that was a really poignant scene that really sums up the attitude toward bullying in our culture – it’s easier to overlook it and pretend it’s not there.

You’re a hundred percent right, and it’s very troubling.

With social media becoming so prevalent and the ability to hide behind the anonymity of the internet, do you think the problem has become worse than when you were younger?

You’re getting at something that we were really thinking about when we were making this film, and that’s how we address social media and the internet presence of bullying. It was only the nascent levels of that when I started school, so in order to keep it realistic for us, we tried to avoid those things as much as we could. But I think that in person, face-to-face bullying is still exactly the same as it was. In fact, that’s what we learned when we were in those high schools. People were like “yes, this is right, you’re doing this right.”

But the psychological elements of online alienation, I think, are even more powerful than the type of alienation that we would’ve felt when we were young, certainly. And in many ways, the film address that through Matt’s kind of “avatar” presence through his own movie, this sort of version of him that he wants to be, or this version of him and Owen that can transcend this.

And I think what we’re seeing now is high school kids making versions of themselves on the internet, and then other kids tearing those avatars to shreds. It’s like you create an emotional doll of yourself on the internet, and it’s almost more painful to see that shattered by other kids online.

You were able to shoot in a real high school, and a lot of people in the film are real students. How supportive was the administration when they realized what kind of film you were shooting?

Well, we had to let them know up front. It was quite a process to get a school to agree to that. We told them “listen, we’re trying to make a movie about real bullying, and show real students, and try to get at the problem from the inside.” Once we found a school that was kind of cool with that, it was very easy. They never asked us any questions, and everybody kind of worked with us.

Owen and I could just be in an environment shooting. I never talked with the camera crew, they never really needed to talk to me, we just went through our day trying to drum up as many scenes as we could think of on the fly. And I think in the end, the kids who’ve seen the film and who are in it are super happy, because we tried to show everybody in sort of the best possible way. Nobody really comes off looking bad, the bullies are actors that we set up, so it’s not like anybody looks like a jerk.

You mentioned shooting and coming up with scenes on the fly – the movie didn’t really have much in the way of a traditional script, right?

None. We had cue cards – I’m actually looking at the cue cards right now for our new movie – and we just put them on a wall. And then we just kind of moves those cue cards around to give us a sense of the structure. Like the cake scene, we would have “Cake Plan Scene” on a card, and it would be like “Owen gives the cake to the Dirties” and the next scene would be like “Matt is upset that the plan went wrong in his mind.”

So little tiny things, and then we would just shoot those scenes, and in editing and rewriting we’d change the order, maybe create new scenes, all kinds of things like that. It’s really great, it’s a ton of fun to shoot that way, and very easy.

Could you see yourself working on a movie in a more traditional manner, or do you want to continue making films this way?

I’m making a movie now about the moon landing, which is gonna be shot exactly the same way as The Dirties, but after that I’m gonna do a remake of Lord of the Flies, which is gonna be shot very traditionally. It’ll be shot a lot like a Terrence Malick movie, very straight, scripted, with some of the tricks from this style of filmmaking, but not many. I’ll only make movies like this that I can act in, so as soon as I can’t act in my own movies anymore, I’ll stop.

So you’re gonna remake Lord of the Flies?

Yeah, I’m gonna do a modern version of it, very much in keeping with the books, but I’m gonna do it for audiences today. It’s gonna be amazing, it’s gonna be nuts. I’m gonna do the entire first act in a private school, before they actually land on the island. And they’re not gonna be twelve-year-old British boys, they’re gonna be like fifteen or sixteen, like really hardcore kind of tough guys. It’s gonna be amazing.

And it’ll all be very modern, like they’ll make spears out of broken iPad screens and shit like that. It’s gonna be wicked. Super, super violent, kind of in the world of Battle Royale, which is so crazy because Battle Royale is a total ripoff of Lord of the Flies. It’ll be dark, but still a movie that all kids can see. It’ll be amazing.

Is that something you’ve got set up at a studio, or are you doing it on your own?

It’s sort of in its early stages, but yeah, it’s being done through a studio right now. But that may change. It’s a ways off – I’ve gotta make this moon movie first. The moon movie will be done by Sundance next year, and Lord of the Flies I’m hopefully doing right after.

We’re just about out of time, so let me ask you – when people see The Dirties, what do you hope they take away from it?

The main thing is just an idea of tolerance. For me, the idea that the news paints people who commit these types of crimes as psychopathic, soulless monsters is super troubling. I looked at home video footage of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, and when I see those guys making movies or joking around, I see something very close to what I was like when I was that age. And the idea that these guys just get completely written out of the book of humanity I think is kind of preventing us, as a society, from taking a step forward in the right direction of how to solve these types of mental illness problems.

So if people watch this movie, and just for a second can see this issue from a slightly different perspective, I’m happy. I know a lot of young people will see and think about how easy it was to make a movie, but for other people who maybe aren’t film students or aren’t born of the same generation, I’m just hoping that maybe they’ll see this issue slightly differently. I know that’s sort of a lofty goal, but that’s what I’m hoping.

The Dirties is currently playing in limited theatrical release, and is available via most On-Demand platforms.